“A Christmas Carol” and Luigi Mangione

Why it’s crucial that we remember Scrooge was shown mercy and given time to repent — even despite his very real ills toward others

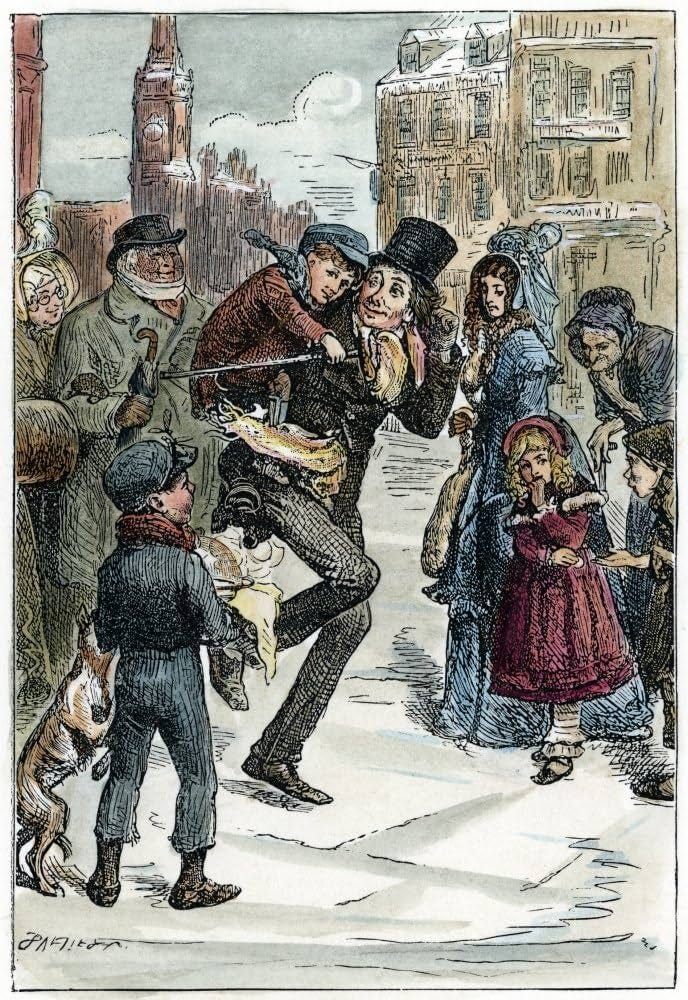

If Charles Dickens had written “A Christmas Carol” differently, we might be telling and retelling a story in which poor Bob Cratchit decides he’s had enough, takes a pistol to his boss’s home, and shoots Scrooge. Cue everyone in Victorian London singing “Ding, dong, the witch is dead.” Fortunately, that is not the version he wrote.

Dickens insisted that he was writing a fairytale about the ills of 19th-century industrial capitalism. He had a deep sense of justice and was distraught about the plight of those who were being forced now to work too hard for too little.

In particular, according to CU Denver Instructor of English Jody Thomas, “Dickens was very, very concerned with child welfare; in fact, that seems to be the main reason he wrote the book. He wanted to say something about the harsh treatment of children in Victorian England.” Tiny Tim makes a lot of sense in that context.

We are today in a situation in which many celebrate an act of vigilante justice toward someone they equate with Scrooge. Luigi Mangione is praised in many circles of social media as a hero for shooting the CEO of United Healthcare. And I think that’s why we need “A Christmas Carol.” We need to revisit the idea that justice and mercy can coexist. It is possible to be deeply angry about the way people are treated by a person or a system and still give the perpetrator the freedom to repent, change, and grow.

My focus is fairytales and the human heart rather than economics, and so I will leave aside here the question of whether UHC is just or unjust. The point is, whatever one believes about the righteousness (or lack of thereof) of UHC, there is a dark and ugly part of our own hearts that wants to see the perpetrator of injustices suffer. Luigi Mangione is being celebrated for taking matters into his own hands, and I’d argue that the part of us that celebrates such a thing is a dark and monstrous part of the heart which we need to take a good look at. Justice is possible and doesn’t require execution-without-trial. That’s the road to a culture of mass unforgiveness.

We are in many ways already in that culture of mass unforgiveness, though on a smaller scale than those of Revolutionary France or Russia. Many commentators have written about the fact that “cancel culture” is essentially public ostracism-without-trial. When someone is “cancelled,” there is usually little opportunity to defend their good name and little chance given to them to try again and rejoin society, even when they have apologized. For many people, the apology and the repentance aren’t enough. This person needs to be actively purged from society.

It is now, though, that we find Unforgiveness Culture bleeding over into real violence. Social media accounts are full of people calling Mangione “their hero,” “a hottie,” or “slaying that orange jumpsuit.” Some of this is tongue-in-cheek but some is not. And it’s the part that’s not that we need to examine within ourselves.

That’s why we need “A Christmas Carol.” We need the catharsis of being angry at the genuine ills of Scrooge toward other people and the release of forgiving him and allowing him to repent and grow.

“A Christmas Carol” and Forgiveness Culture

Dickens wrote the short story “A Christmas Carol” during the Victorian period in England, in which Christianity was still culturally dominant but industrial capitalism was on the rise. As Jody Thomas writes,

“When Dickens was writing A Christmas Carol, English society was rapidly changing in response to the Industrial Revolution. England was changing from an agricultural society to one where many people were moving to the cities and working in factories. The earlier tradition among the Georgians was for nobility to host feasts in their manors, some lasting up to twelve days, for their tenant farmers, but that practice had begun to fall out of favor during the Victorian era as a result of industrialization and urbanization. And there was an uncertainty about how to celebrate Christmas in the cities.”

“A Christmas Carol was very influential in demonstrating to the Victorians that they could uphold the generosity of the Georgians’ way of celebrating Christmas, the idea that the wealthy needed to provide for the poor, and move it into the city and into the private home. Instead of a being a communal feast or party, the celebrations became smaller, more intimate, and focused on families and children. Amid their changing world, A Christmas Carol showed the Victorians wonderful images of warm family celebrations and of people sharing their good fortune.”

And so, we have the tale of Scrooge. And oh, Scrooge is terrible. Anyone who works for any kind of modern corporation will likely find catharsis in reading about Scrooge as well, knowing at least one other person who has had similar experiences.

He denies his employees time off. Even Christmas, he says, should be a work day. He denies them fair wages, with the result that his employee Bob Cratchit’s son Tiny Tim is on death’s door because the family can’t afford proper medical care. He refuses to give anything to charity. It goes beyond him just hating Christmas and shouting “Bah! Humbug.” He’s not a grumpy, but kindly, old man. He is truly perpetrating injustice upon his workers.

But he is given the chance to repent. Dickens, still very much writing in a context of Christianity in the culture, isn’t telling a story about the workers rising up in a revolution and taking justice into their own hands. He is instead telling a story in which change and growth are possible, and we can give every person the freedom to find it within to in themselves.

This is not to say no justice is possible. Aside from the eternal justice that Dickens shows us is awaiting Scrooge, in our own society, we do have non-executionary means of justice. If Scrooge were alive today and had violated labor law, he still has the chance to repent in prison because at least he is still alive.

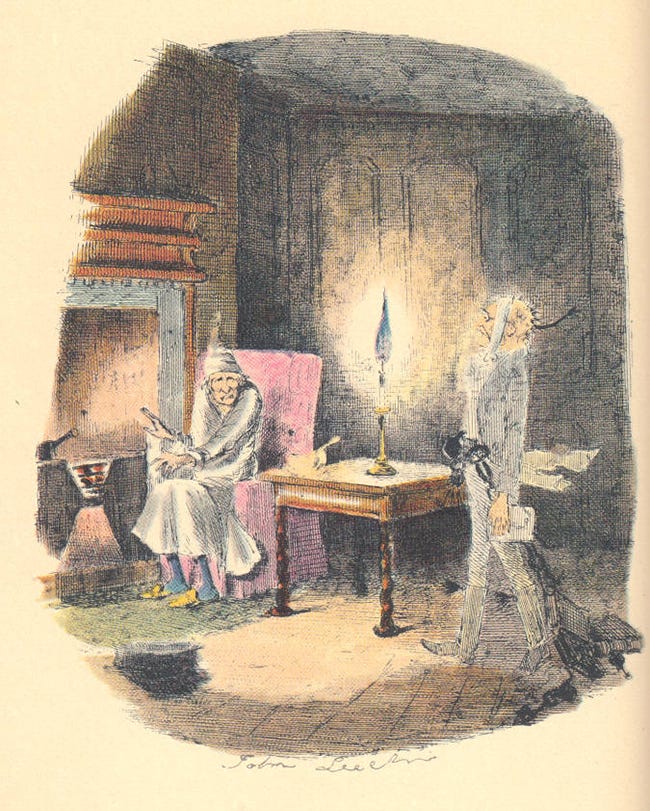

So his repentance is prompted by the nighttime visitations of the ghost of his late business partner, the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the Ghost of Christmas Future. Each of these ghosts is here to show him the consequences of his ill-treatment of others — both to them and to himself. They show him the horrifying fate he can still hope to avoid.

Scrooge does repent, and he does begin to find it in his heart to send his employer a Christmas turkey and encourage him to spend time with his family. He begins to donate to charities. And he begins to live a life of love and communion with others, the kind of life he had for so long rejected.

This is a vision of transcendence. I call it “Forgiveness Culture.” This is hopeful. John Truby has noted that “A Christmas Carol” belongs in Horror and Fantasy genres, both of which show us through supernatural means the depths of our lives; the story we are given here is a story of the horrors of our actions, yes, but also of the possibility for betterment.

In Forgiveness Culture, people’s repentance is welcomed and at least, if nothing else, possible. The possibility is left open for them. I am well aware that England at the time practiced capital punishment, but as part of their justice system, contingent on a trial, and certainly not by a vigilante deciding to take justice into his own hands. As Dickens writes in his novel Great Expectations,

Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts. I was better after I had cried, than before--more sorry, more aware of my own ingratitude, more gentle.

And so, “A Christmas Carol” ends with Scrooge reintegrated into the society he had shunned, making amends for the ills he had caused.

Unforgiveness Culture

Unforgiveness Culture, on the other hand, is wrathful. It wants to see justice meted out without trial, defense, or jury, for it doesn’t believe those institutions capable of serving true justice. Justice is instead for the wise public, for those who are the gatekeepers of society or have “had enough.”

Our culture right now is seeing an influx of admiration (though not from everyone) of Luigi Mangione, for murdering the CEO of United Healthcare. From #FreeLuigi memes to comparisons with the Super Mario Bros. to “thirst edits” about his physical appearance, it is a fascinating look at American culture.

As always, my perspective is that fairytales help clarify things. “A Christmas Carol” is a kind of fairytale, and so, whether UHC is right or wrong, the question to me is what we do with the wrath in our own hearts. Do we valorize vigilante justice and murder? Or do we seek those means of justice which still allow the perpetrator to repent?

I’m a big fan of

’s recent essay, “The Moses Option.” He too is concerned about social ills and injustices that permeate culture, but his proposed solution begins with repentance. It begins with taking a look at our own hearts.Final Thoughts

I cannot claim to have any answers about what to do with our healthcare system. Personally, I do think it is broken. But that isn’t the purpose of The Enchanted Window, in which I’m here to use stories to look more deeply into the human heart.

Instead, as Dickens is writing in a Christian context, I will leave us with a Christian quote:

From the Gospel of Matthew:

Then Peter came to Jesus and asked, “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?”

22 Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times.[a]

23 “Therefore, the kingdom of heaven is like a king who wanted to settle accounts with his servants.24 As he began the settlement, a man who owed him ten thousand bags of gold[b] was brought to him.25 Since he was not able to pay, the master ordered that he and his wife and his children and all that he had be sold to repay the debt.

26 “At this the servant fell on his knees before him.‘Be patient with me,’ he begged, ‘and I will pay back everything.’ 27 The servant’s master took pity on him, canceled the debt and let him go.

28 “But when that servant went out, he found one of his fellow servants who owed him a hundred silver coins.[c] He grabbed him and began to choke him. ‘Pay back what you owe me!’ he demanded.

29 “His fellow servant fell to his knees and begged him, ‘Be patient with me, and I will pay it back.’

30 “But he refused. Instead, he went off and had the man thrown into prison until he could pay the debt.31 When the other servants saw what had happened, they were outraged and went and told their master everything that had happened.

32 “Then the master called the servant in. ‘You wicked servant,’ he said, ‘I canceled all that debt of yours because you begged me to. 33 Shouldn’t you have had mercy on your fellow servant just as I had on you?’ 34 In anger his master handed him over to the jailers to be tortured, until he should pay back all he owed.

35 “This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”

Amen. God give us strength to forgive from the heart.

Enjoyed this article? Consider subscribing or leaving a tip. It’s never expected, always appreciated, and helps me keep writing. Thank you!

Some profound reflections. It seems you might have been chosen to tell a tale of some secret Santa, some covert St. Nick, a canceled corporate monster who refuses to make a show of his repentance, a man dumb before his virtuous public shearers and shamers, a man who withers at the kindness of his Tim, and who revels in the reproach of his fellow man. You know, now that I think about it,….a story that runs on similar rails was written decades ago. Magnificent Obsession, by the same author as the Robe. It might just be time for a new Magnificent Obsession, and you might have the right gift, insights and inspiration to make a tale of it. Consider it a friendly challenge.