How Not to Be Human: The Fairytale Horrors of Tom Riddle and Morda

We have two choices as we go through life: to become more human, or less human?

It’s a gorgeous spring season here, with mild warmth and buzzing bees and plenty of opportunities to lay in the grass with friends, looking up at the clouds. We even had a lunch picnic on a weekday not long ago!

There’s a beauty in life worth walking toward — something like Tolkien’s statement in The Hobbit that “if more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

And yet, it’s also worth remembering that there’s an ugliness worth walking away from (indeed, running away from), one which Tolkien certainly does not shy away from revealing to us. There’s the food and cheer and song of the shire, but then there’s also the evil of Sauron, the greed of the Ring-Wraiths, and the depravity of Gollum. What Aragorn says about the Ring-Wraiths, the Nazgûl, is crucial: “They were once men.”

So what if we are all human, the way the Nazgûl started out, and yet there are two paths we can choose to follow? One that leads to becoming more human, and one that leads to becoming less human? We always have a choice: to become more human or less human. We can be more in-tune with our nature and live peacefully with it and with the world around us, or more out-of-tune, living in disharmony with ourselves and with other people.

It’s this latter path I want to discuss today, because I recently finished reading Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles and was struck by how much his evil character Morda reminded me of the Harry Potter series’ Tom Riddle. Both characters choose an everlasting life of death over any acceptance of a death that leads to life. Both try to seal their souls in objects outside of themselves. And both view themselves as fundamentally set apart from humanity and superior to it.

These characters show us how to not be human. There are ways of life that would lead us to become less human — ways of cruelty, possessiveness, greed, and cold-heartedness. So in our quest to be truly human and inhabit a Right-Side-Up reality for ourselves, I want to look at how these characters choose to cement themselves firmly in Upside-Down ways of living. These are the paths we want to stay away from, no matter how seductive they appear.

“We always have a choice: to become more human or less human. We can be more in-tune with our nature and live peacefully with it and with the world around us, or more out-of-tune, living in disharmony with ourselves and with other people.”

These are the paths of fairytale horror. I’m convinced that this is why the genre of horror (or even horror elements) in fiction exist — to wake us up to the existence and possibility of real evil and to give us the weapons and discernment to defeat it.

What is horror? What does it have to do with being human?

In The Anatomy of Genres, John Truby writes that horror as a genre is so primal to us because “the major distinction governing human existence is life versus death.” He also notes that while horror as a genre (in the way we know it) is relatively recent, horror elements have been embedded in myths for thousands of years. Think, for example, of the Minotaur, the human-eating monster that lives deep in a labyrinth. Or of Medusa the Gorgon, who can turn a person to stone with just one look.

Pet Truby, here’s how Horror compares to its Speculative Fiction sisters, Fantasy and Science Fiction (emphasis mine):

The main goal of [Horror] is to force us to confront death. To pry our eyes open and shove death in our face. Whether this highly emotional approach induces us to see our end honestly and make real changes to our lives is another question.

Horror is part of a major family of genres known as “Speculative Fiction,” which includes Fantasy and Science Fiction. These three genres are about projecting and abstracting in the extreme. Fantasy projects a character into a fully detailed imaginary world so she can learn how to live. Science Fiction creates a society and culture, with special focus on the science and technology by which the world operates. Horror creates a character out of the most dangerous of all opponents: death itself.

On a moral level, and more to the point of Morda and Tom Riddle, Truby argues that the moral claim horror is making is this: “you must first face past sins and then make amends to anyone you have harmed. It goes further, saying: if you try to beat death, you will cause even greater destruction to those you care about most. This lesson is usually not learned.”

The key question of the form, he writes, is: “What is human and what is inhuman?”

While horror has many sub-genres and twists on the genre (combining it with other genres or turning some elements on their head), in the two respective examples we’re discussing here, JK Rowling and Lloyd Alexander are working with fairytale horror. That is, they are fusing horror with “foreign, mysterious, or ‘Old World’ locations,” making the horror believable. They are using their mythical worlds of Hogwarts and Prydain to show us how humans can become monsters.

Tom Riddle and the Horrors of Horcruxes

Tom Riddle’s main quest is to beat death. It’s his throughline, his motivation, his primary goal. Throughout the Potter books, he and Harry Potter are foils, treating death very differently and thereby either securing for themselves a “less human” existence or a “more human” existence. Riddle (or Voldemort, as he’s later known) becomes less human by trying to defeat death at the expense of other people. Harry becomes more human by giving himself up voluntarily to death for the sake of other people.

Riddle, like Harry, is raised in negligent, abusive circumstances. Rowling is no determinist, and as she has Dumbledore say in Chamber of Secrets, “It is our choices, Harry, that tell us what we truly are.” She is not setting up Tom Riddle to become sub-human by being born in awful circumstances but by choosing a path leading to death at every meaningful step of his life.

Little Orphan Tom grows up detesting death from the very beginning, seeing it as shameful weakness. When Dumbledore comes to tell him he’s a wizard, he speculates on his parentage and says his mother “can’t have been magic” because “she died.” To Riddle, to die is to be vulnerable, pitiful, and shamefully human.

We are told as the tale of his upbringing goes on that he detested anything that made him like other human beings — including his name. Debriefing with Harry the memory they have just seen of the young orphan Riddle, Dumbledore says:

“ ‘Firstly, I hope you noticed Riddle’s reaction when I mentioned another shared his first name, ‘Tom?’’

Harry nodded.

‘There he showed his contempt for anything that tied him to other people, anything that made him ordinary. Even then, he wished to be different, separate, notorious. He shed his name, as you know, within a few short years of that conversation and created the mask of ‘Lord Voldemort’ behind which he has been hidden for so long.

Riddle’s desire to defeat death and be set apart from humans leads to his ultimate crime: the splitting of his soul through multiple murders. In his quest for immortality, he creates Horcruxes, magical objects that contain fragments of his soul, so that his soul exists outside of his body and he cannot be killed. The process of splitting the soul is the act of murder. Murder makes Riddle less human. As Professor Slughorn explains to him:

“You must understand that the soul is supposed to remain intact and whole. Splitting it is an act of violation, it is against nature.”

Slughorn then proceeds to explain to Riddle that this inhuman act of splitting one’s own soul can only be accomplished through the supreme evil — murder. And it is Voldemort’s deep desire to avoid death that leads him to entertain the prospect, even as a teenager, of murdering six people to create six safeguards against his physical death.

We are given clues throughout Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince that Voldemort’s descent into deeper evil also makes him progressively less human. When the young orphan Riddle is told he is a wizard, Rowling describes his wild happiness, driven by greed and pride, as “almost bestial.” After he has committed several murders on his road to becoming Lord Voldemort, Harry describes the adult Tom Riddle (witnessing him in one of Dumbledore’s memories) as such:

“His features were not those Harry had seen emerge from the great stone cauldron two years ago: They were not as snakelike, the eyes were not yet scarlet, the face not yet masklike, and yet he was no longer handsome Tom Riddle. It was as though his features had been burned and blurred; they were waxy and oddly distorted, and the whites of the eyes now had a permanently bloody look, though the pupils were not yet the slits that Harry knew they would become.”

By the end of his transformation, Voldemort has become something almost entirely other than human, internally as well — he has murdered and tortured scores of people, burned away whatever human empathy he may have had, banished the thought of remorse, and calloused his heart.

Even his army is made up of the Inferi, corpses he has reanimated. His Death Eaters kill mercilessly in the name of defeating death. But those who do his bidding are, whether physically, morally, or spiritually, the dead, not the living.

Morda the Merciless

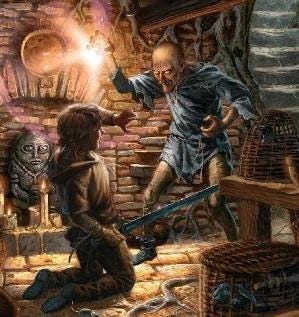

Turning to the Prydain Chronicles, Lloyd Alexander gives us a chilling horror villain in Morda. Our hero, Taran, on a quest with his friends to find his true identity, comes face-to-face with this “skull-like” man in volume four of the series, Taran Wanderer.

Morda, like Voldemort, has chosen to encase his soul in an object outside his body. In Morda’s case, it is a finger bone; he has enchanted the bone to contain his soul and then hidden that bone high up in a tree. Taran finds the bone but only comes to understand its true significance while battling Morda, who is mercilessly turning all his friends into beasts and is about to turn to Taran next.

The first description of Morda we are given is all death and decay, no sign of life (and very much the stuff of nightmares):

“A bony hand gripped his throat. In his ears rasped a voice like a dagger drawn across a stone. ‘Who are you?’ it repeated. ‘Who are you?’

…As his sight cleared, [Taran] saw a gaunt face the color of dry clay, eyes glittering like cold crystals deep set in a jutting brow as though at the bottom of a well. The skull was hairless, the mouth a livid scar stitched with wrinkles…in the dimness Taran could make out little more than a low-ceilinged chamber and a fireless hearth filled with dead ashes.

…More than the wizard’s words filled Taran with horror. As he watched, unable to take his own eyes away, Taran saw that Morda’s gaze was unblinking. Even in the candle flame the shriveled eyelids never closed; Morda’s cold stare never wavered.”

The inner reality that this all represents, though, is even more horrifying. Like Tom Riddle, Morda has set out on his course that leads to a deathlike existence by despising the human race and seeking to make for himself a place apart from (and above) it. He has little concern for human life, telling Taran coldly:

“Think you the life or death of or of you feeble creatures should concern me? I have seen enough of the human kind and have judged them for what they are: lower than beasts, blind and witless, quarrelsome, caught up in their own small cares. They are eaten by pride and senseless striving; they lie, cheat, and betray one another. Yes, I was born among the race of men. A human!’ He spat the word scornfully. ‘But long have I known it isn’t my destiny to be one with them, and long have I dwelt apart from their bickering and jealousies, their little losses and their little gains.’”

Like Tom Riddle, Morda begins down the path of evil by despising the weakness of other humans and seeking to be set apart from them. But also like Riddle, the longer he traverses down that path, the further it leads into deeper and deeper evils and less and less humanity. The next steps on the road are murder and theft.

Taran realizes with horror that Morda had long ago murdered the mother of his true love Eilonwy. Eilonwy’s mother Angharad had traveled across Prydain desperately looking for her baby daughter, whom we ultimately learn was kidnapped by the witch Achren. The Princess Angharad unfortunately came across Morda on her quest.

Taran learns of Angharad’s fate from Morda:

“‘As for her who called herself Angharad of Llyr,’ the wizard continued, ‘of a winter’s night she begged refuge in my dwelling, claiming her infant daughter had been stolen, that she had journeyed in search of her.’ The wizard’s lips twisted. ‘As if her fate or the fate of a girl child mattered to me. For food and shelter she offered me the trinket she wore at her throat. I had no need to bargain; it was already mine, for too weak was she, too fevered to keep it from me if I chose to take it.’

In loathing Taran turned his face away. ‘You took her life, as surely as if you put a dagger in her heart.’

Morda’s sharp, bitter laugh was like dry sticks breaking. ‘I did not ask her to come here. Her life was worth no more to me than the book of empty pages I found among her possessions.’”

This is the same path Tom Riddle chooses — disregard for the lives of human beings, murder, and the theft of the objects most valuable to them. They are both acting as Nietzsche’s supermen, embodying the life of: “I can, so I will. Who will stand in my way?”

The trouble is, making oneself less than human is, in both of their cases, highly unstable in addition to evil. Voldemort’s ultimate fate is to have his Horcruxes all destroyed by his enemy (who, unlike him, isn’t afraid to die if it means the safety of others) and then to be reduced to the death he so feared. Morda’s fate, bone-encased soul destroyed by Taran, is to crumble “like a pile of broken twigs.”

We always have a choice

What makes Voldemort and Morda the nightmares of fictional horror that they are is their desire to become less human. It is both their desire and the ultimate consequence of their actions. Both despise people and seek to be set apart from them. Both disdain the lives of others as worth less than their own. And both are so terrified of the ultimate human vulnerability, death, that they will do anything to run from it, including subjecting countless others to it.

I think we have a choice, every day, in big things and small things, to become either more human or less human. The tales of encasing one’s soul in a murder-begotten object are larger-than-life, to be sure. But every day, we face numerous possibilities to look down on people, to deem ourselves better and our lives more worthy, and to create for ourselves identities that we imagine to be greater than those of others. There are so many ways to make our hearts more calloused.

There are also ways to become more human. We may not have Harry Potter’s choice in front of us to walk into death for the sake of others, or Taran’s heroic choice by the end of the series to remain in a broken world and help its people rather than sail off into the sunset. But we do have so many opportunities to show mercy, love, kindness, joy, peace, and humility. It’s the sum of those choices that move us further down the road to becoming more fully human.

I’m forever grateful we have these stories to show our hearts these choices and their consequences so vividly. By imbibing what they have to say to us and living it, we can start inhabiting a Right-Side-Up, well-ordered life.

Very good article, thank you.

Another fine description of someone losing his humanity by seeking to escape death is the lemur in Margaret Mahy's "The Changeover".

"... I fell in love with the idea of human sensation, you see. I couldn’t, no I couldn’t give it up. And, you can’t imagine, you take it all for granted — it’s yours by right so you never think: the pleasures of touch and taste. Your skin alone — your skin affords you such— rapture!” cried Mr Braque, clawing at her. What remained of his face twitched all over, a tiny, violent quivering as if he had just been killed. “To eat a peach, picked straight from the tree and warmed by the autumn sun, to bite a crisp apple — the first juice — a revelation— or to feel the sun on bare skin. Salt! Salt!”

So he has learned to steal lives.

The book contains many discussions of this unfolding horror, and the heroes reflect upon how it might happen to themselves (perhaps already is quietly happening), and how to avoid it.

This is such a great post