Strength and Softness: Britomart, the Lady-Knight

All these dichotomies about femininity miss the point

I first discovered The Faerie Queene from JK Rowling, under her pen name Robert Galbraith (by which she writes her Cormoran Strike detective series). Specifically, I was intrigued by the fact that all of the epigraphs and much of the central plot of her Strike novel Troubled Blood were from The Faerie Queene. And in these epigraphs, she reintroduced her main heroine, detective Robin Ellacott, as a version of the Lady-Knight Britomart.

The Faerie Queene is an intimidating (and very long) work — the language is archaic, the storytelling structure is allegorical, and the stanzas require a kind of narrative meter (like Shakespeare or Homer) which we’re not at all used to in our reading. But Rowling’s mapping of this great poem to a modern detective novel gave me the boldness to try and approach it, too.

And there are good places to start, without jumping right into the original poetic text itself. Some of these places include the prose versions by Mary MacLeod and Jeannie Lang, respectively.

In Troubled Blood and The Faerie Queene, I first encountered Britomart. She defied all the categories our modern age so frequently uses to divide and label women — she was neither fully “trad,” nor fully “progressive.” She was strong and soft. She was on a quest, but it was in pursuit of true love. She was a heroine who could hold her own in a fight and also need the love of her beloved. I was astounded to find that this can (and does) all coexist in her. She is now one of my favorite fictional characters.

I’d like to invite you to take a deeper look at Britomart, this 16th-century Lady-Knight, because she can show us a way out of some of our less fruitful conversations about femininity. There IS, it turns out, a kind of femininity that fuses strength and softness, independence and love. It is possible. We don’t need to settle for a false dichotomy between bland girlbosses who “don’t need men” and waifish fainting ladies. Britomart is an incredibly nuanced heroine.

Britomart and the context of The Faerie Queene

The Faerie Queene’s exalted view of women should be read in the chronological context of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. Edmund Spenser wrote his epic poem in the 16th century and explicitly dedicated it to Queen Elizabeth. The English Queen is, in fact, his allegorical model for the Queen of Faerie Land herself, Gloriana.

Each book of The Faerie Queene represents a particular virtue, and Book III, of which Britomart is the heroine, is focused on Chastity. She is in fact described as the knight who is fighting for Chastity. To understand what is meant by Chastity in this context, it helps to understand what it has traditionally meant. Although the word “chastity” in modern times often conjures up images of complete abstinence or lack of sensuality, it is understood a little differently in The Faerie Queene. Chastity here is more of an “ordered love,” one not based on lust and that makes someone wholesome and integrated rather than disintegrated. CS Lewis, who studied Spenser extensively, put it thus:

Chastity is the most unpopular of the Christian virtues. There is no getting away from it; the Christian rule is, ‘Either marriage, with complete faithfulness to your partner, or else total abstinence.’

It is this core faithfulness for which Britomart fights, including on behalf of other people. More on that in a bit.

Importantly as well, our Knight of Chastity is a warrior — it makes her whole and strong, rather than passive. She is a fully integrated person, body, will, mind, heart, and soul. According to Vassilios Papavassiliou, who is writing here about chastity in a Christian context but derived as well from the Ancient Greek principle of sophrosyne that preceded it:

the true and full meaning of the Greek word for chastity, sophrosini, is “wholeness” or “wholemindedness.” Chastity is therefore a state of being in which the soul and body work together as one.

This is Britomart. She is strong on behalf of love, with a soul and body cooperating toward this will.

Strength in search of love

Oftentimes, these days, we think about “strong heroines” explicitly as the ones who either don’t need love or, at very least, aren’t looking for it. We tend to either fall into one of two sides of an extreme — either we want “strong women” who aren’t looking for the love of a man as any kind of driving goal, or we want “traditional women” who are seeking love and connection but are willing to defer strength (particularly physical strength) to men.

One of the many reasons I love Britomart so much is that she does both, and it is completely natural to her. She is a knight (and a very skilled one, at that), but her whole quest kicks off because she is looking for true love.

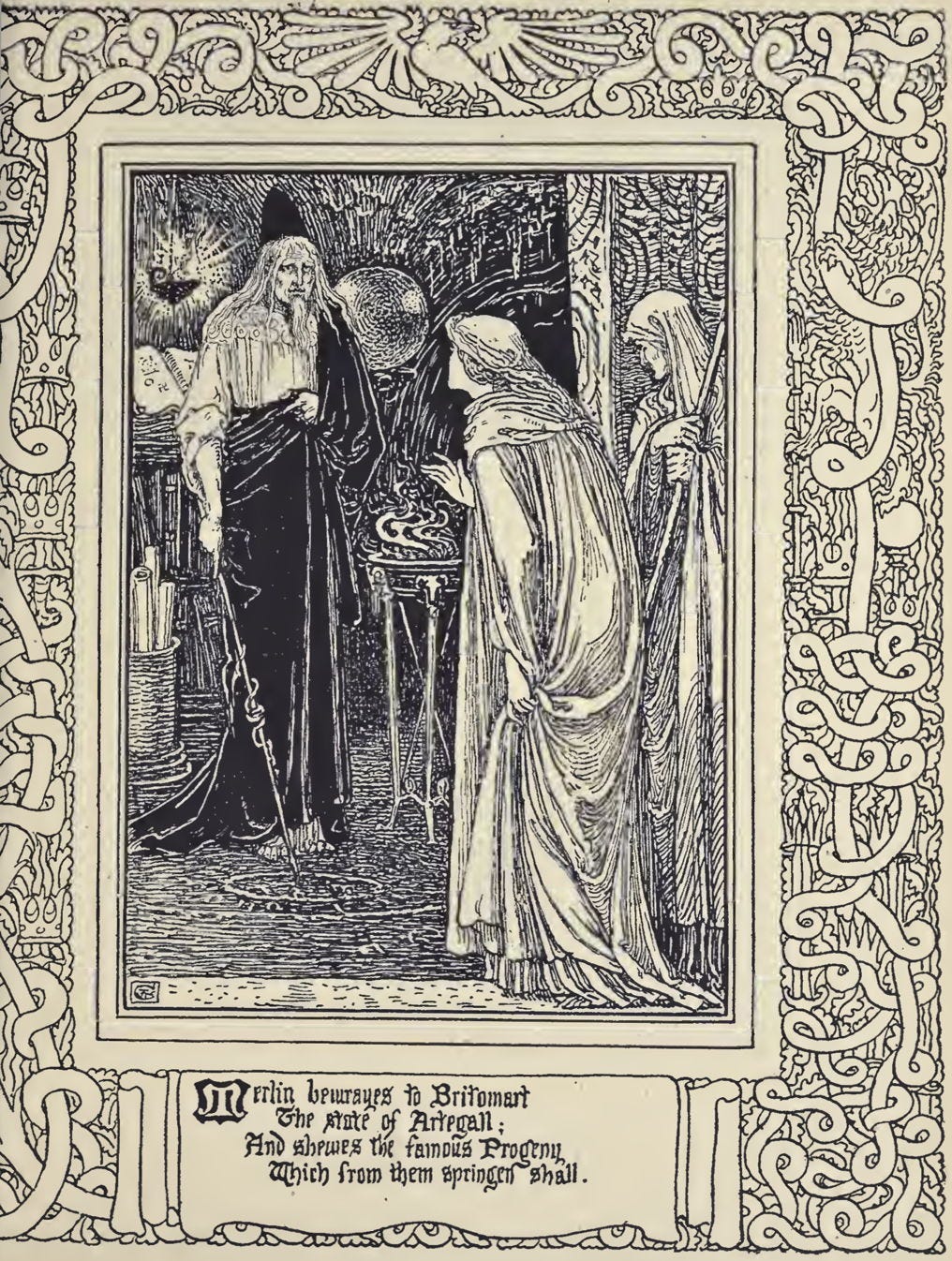

Britomart’s quest begins when she, growing up as the kind of girl who enjoyed knight-training more than playing with dolls, still very much wants to be married and asks a crystal ball to show her who she’ll marry someday. The crystal ball shows her Artegall, a noble knight who is currently in Faerie land fighting for the Queen, and she falls instantly in love with him. She even begins to despair because she worries he isn’t real! But Britomart goes to Merlin for help, and Merlin, chuckling at the lovelorn goal, tells her that Artegall is indeed real and is in terrible trouble. He then exhorts Britomart to go save Artegall.

And so begins the lady’s quest. She is sent by Merlin off to Faerie land with an enchanted lance that will win any fight, and Britomart does win many, many fights. She is several times mistaken for a man but is no less respected when she takes off her helmet and reveals that she is a woman. (In some cases, the removal of her helmet is met with relief from jealous men who are worried their wives will leave them for this knight).

Britomart finds Artegall, and she finds that they are equally matched in an arena. She defeats him twice when he thinks she is a man, and he almost defeats her during their third fight, but as he is about to strike the final blow to her helmet, the helmet falls off and she is revealed to be a beautiful woman. Artegall in turn falls in love, and the two are married.

To me, this story is much more nuanced and interesting (and real, in a human way) than the way we often treat gender. Britomart, written in the 16th century, is a true heroine who doesn’t fall nearly into the categories we’ve concocted.

The lady-knight in defense of marriage

Britomart also, during her quest, does not just seek out her own future husband but also fights on behalf of other married couples who want to remain faithful to one another. One of these couples is a knight named Sir Scudamour and his newlywed wife Amoret (in some translations, Amoretta).

According to Sir Scudamour, his lady Amoret has been carried off by a terrible magician Busirane and kept in his castle. Britomart is moved by his grief and vows to rescue Amoret or else die trying.

She discovers that Busirane is in love with Amoret and has concocted elaborate magical illusions to persuade her to leave Scudamour and marry him instead. Amoret does not give in and maintains that she has a one true love. The illusions include magical tapestries depicting the exploits of the god Cupid and a procession involving a man pretending to be Cupid and accompanied by people playing allegorical parts, with names like Ease, Desire, Fear, Hope, and Cruelty. Cupid wears a mask and rides a lion and is ultimately followed out by Reproach, Repentance, and Death — all those who accompany false love.

Britomart discovers Busirane with the captive Amoret and threatens him to let her go and undo all the enchantments, or else she will kill him. He complies, the tapestries and the procession all fall away, and Amoret thanks Britomart profusely.

What follows is a kind of touching sisterhood between Britomart and Amoret. They set out to find Scudamour (who has, in the meantime, assumed them dead and ceased waiting outside the castle) and become great friends in the process. This was all three to four centuries before any Bechdel test.

In some ways, I’m reminded of the ways in which Greek mythology had Artemis fight on behalf of women, though in her case accompanied by a good deal more spite. And I can see why JK Rowling would frame her own detective heroine Robin as Britomart, particularly when Robin is trying to solve a cold case that would free a woman from the mystery that surrounded her disappearance forty years prior. Throughout Troubled Blood, in fact, Rowling has Robin defend not only the female victim of the crime at the center of the novel, but also other women who suffered from similar crimes and modern women in her own workplace.

A heroine who loves

We never needed to divide women into boring, reductive categories; we still don’t. In all of our conversations about the heroines we see in pop culture and in stories, there is so much room to be many good things at once — to be soft and strong, loving and independent, chaste and fierce. I can’t help but think that if our culture attempted to tell a modern story about a lady-knight, it would be highly unlikely that she would be questing in search of true love. It wouldn’t fit the script we’ve determined for what a “lady warrior” does. But it needn’t be that way.

Britomart is free to be both warriorlike and tenderly vulnerable, and so are we.