Who is worthy to see the Emperor’s clothes?

A reflection on what we can learn from “The Emperor’s New Clothes” by Hans Christian Andersen

Revisiting the old fairytale “The Emperor’s New Clothes” has been delightful, in large part because I’d forgotten how funny it was. It had been ages since I’d read it. I think when I was a child, the humor in the story might have been a bit lost on me. Here’s a link, if you’d like to read or revisit it: https://andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheEmperorsNewClothes_e.html

There’s a temptation, when we immediately think of this fairytale, to remember it as mostly being about the emperor. “The emperor with no clothes” has become synonymous with “someone in power who thinks he or she has something and is trying to fool everyone else to believe it, when really he or she has nothing.” We typically associate this fairytale with the idea of the emperor as charlatan.

But in reality, when we revisit this fairytale, we find that there are actually two charlatans who concoct this whole scheme, who simply take advantage of the emperor’s existing vanity. The emperor is the swindled more than the primary swindler in the story.

I want to dive into the single aspect of this fairytale I find most overlooked and also most meaningful.

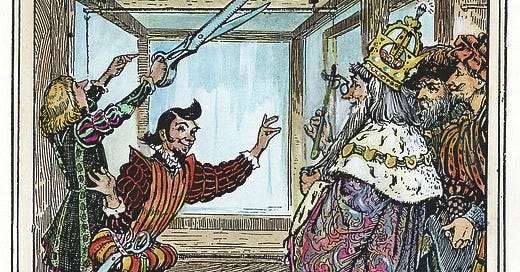

(Illustration by Henry J. Ford)

Hint: It’s not about the emperor. It’s about us. It’s about how every other person in the royal court and in the village responds to the concept of the emperor’s new clothes. And it’s especially about the child and why the child has the courage and common sense to say the things the rest of us struggle with admitting.

I do also need to say upfront that I am not in this moment writing about any particular emperor, be they corporate or political leaders or anyone else. This isn’t a pointed discussion about any particular moment in time. It’s really a timeless discussion about who we are, what we value, and why we as humans (especially as adults) so struggle to admit we can’t see the emperor’s clothes. It’s about our shame and our defenses.

Who is worthy to see these fine clothes?

In the tale, two swindlers present what they describe as “the finest and loveliest fabric” to the emperor, assuring him that this fabric would be invisible to those who were stupid or unworthy of their posts.

The king immediately thinks making clothing out of such a fabric is a fantastic idea. He’ll be able to sort the wheat from the chaff! He’ll know who in his court is actually stupid or unworthy of their posts, because they won’t be able to see the fabric! He readily agrees to the swindlers’ terms and gives them a sum of money to craft clothing from this fabric.

When the time comes that the swindlers want to invite the emperor to see their work-in-progress, he is afraid to go. The question he asks himself is all too human:

“What if it’s invisible to me? What if I myself won’t be able to see the fabric?”

This kernel of doubt is enough for him to send someone else in his stead. He chooses a trusted minister, believing that that man will certainly be able to see the fabric.

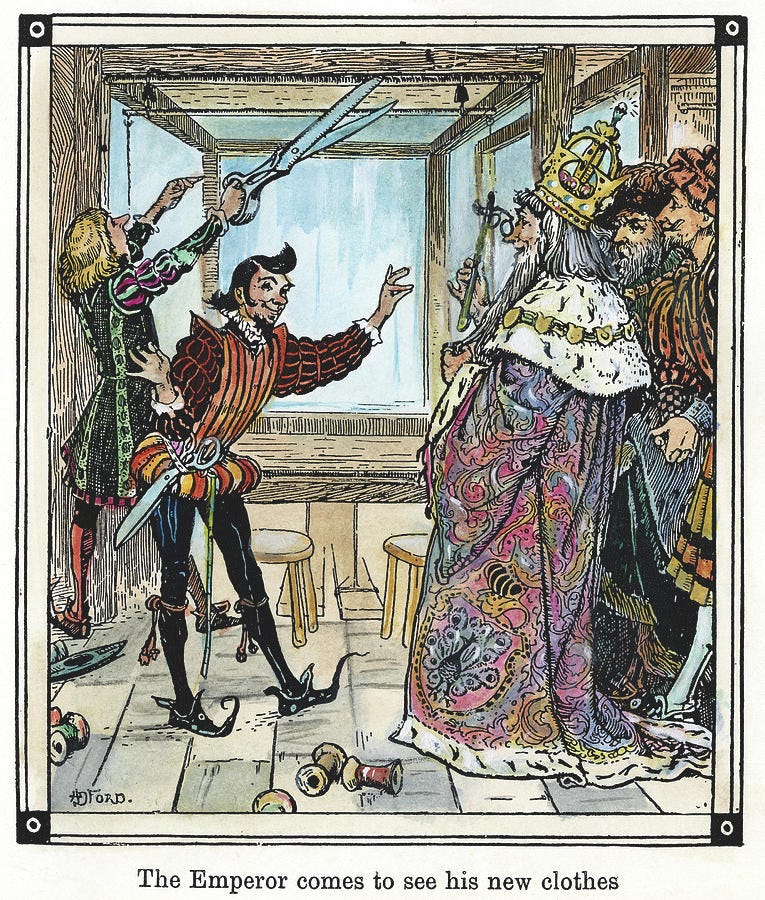

When the minister arrives at the swindlers’ workroom, he is shocked to discover that he can’t see the fabric. Let’s take a close look at his internal monologue here, his thought process as he’s shown the empty loom:

So the honest old minister went to the room where the two swindlers sat working away at their empty looms.

"Heaven help me," he thought as his eyes flew wide open, "I can't see anything at all". But he did not say so.

Both the swindlers begged him to be so kind as to come near to approve the excellent pattern, the beautiful colors. They pointed to the empty looms, and the poor old minister stared as hard as he dared. He couldn't see anything, because there was nothing to see. "Heaven have mercy," he thought. "Can it be that I'm a fool? I'd have never guessed it, and not a soul must know. Am I unfit to be the minister? It would never do to let on that I can't see the cloth."

"Don't hesitate to tell us what you think of it," said one of the weavers.

"Oh, it's beautiful -it's enchanting." The old minister peered through his spectacles. "Such a pattern, what colors!" I'll be sure to tell the Emperor how delighted I am with it."

He doesn’t want to look stupid. He doesn’t want anyone to think of him as unfit for his post. And so the “honest minister” lies to the emperor and extols the virtues and beauty of the fabric he hasn’t seen.

(Illustration by Edmund Dulac)

This continues as more and more courtiers are sent to remark on the fabric, and all of them pretend they’ve seen it. No one can bear to be thought a fool or unworthy.

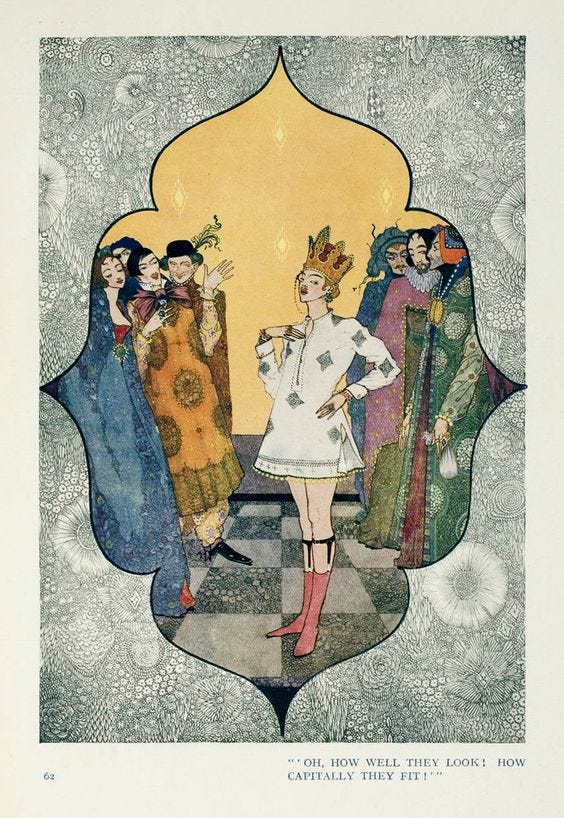

Finally, it is the emperor’s turn to see it. And by now, the groundwork has been laid — everyone in his court has told him how beautiful the fabric is. If he admits he can’t see it at this point, then he is admitting he is stupider and less worthy than everyone else at court. So he lies too. And this is how we end up with the emperor in a procession throughout town wearing no clothing.

Even the villagers feel compelled to pretend to see the clothing. They’ve heard tell of this magic fabric that reveals stupidity or unworthiness, and not a single one of them wants to be seen as either of these. The only one who is capable of pointing out the truth is an un-self-conscious child. Finally, the truth catches fire as people admit that the child might be right.

So what is going on here? Why are these bevies of people all unwilling to admit that the looms are empty, that the fabric isn’t there, that the clothes aren’t real?

Shame, ego, and defensiveness

Everyone except the child has something to prove. They all have reputations, beliefs about themselves, and egos in which they are invested. Take a look at each of their rationales:

The honest minister: "Heaven have mercy," he thought. "Can it be that I'm a fool? I'd have never guessed it, and not a soul must know. Am I unfit to be the minister? It would never do to let on that I can't see the cloth."

The trustworthy official: "I know I'm not stupid," the man thought, "so it must be that I'm unworthy of my good office. That's strange. I mustn't let anyone find it out, though." So he praised the material he did not see.

The two officials in the same room: “Magnificent," said the two officials already duped. "Just look, Your Majesty, what colors! What a design!" They pointed to the empty looms, each supposing that the others could see the stuff. (Emphasis mine)

The emperor: “Am I a fool? Am I unfit to be the Emperor? What a thing to happen to me of all people! - Oh! It's very pretty," he said. "It has my highest approval." And he nodded approbation at the empty loom. Nothing could make him say that he couldn't see anything.”

The emperor’s retinue: “His whole retinue stared and stared. One saw no more than another, but they all joined the Emperor in exclaiming, "Oh! It's very pretty," and they advised him to wear clothes made of this wonderful cloth especially for the great procession he was soon to lead.”

The noblemen: “The noblemen who were to carry his train stooped low and reached for the floor as if they were picking up his mantle. Then they pretended to lift and hold it high. They didn't dare admit they had nothing to hold.” (Emphasis mine)

The villagers: “Everyone in the streets and the windows said, "Oh, how fine are the Emperor's new clothes! Don't they fit him to perfection? And see his long train!" Nobody would confess that he couldn't see anything, for that would prove him either unfit for his position, or a fool.”

Everyone here is worried about two things:

“Am I really a fool? Am I unworthy?”

“Well if I am, then no one can find out about it. I can’t be exposed as a fool or unworthy.”

Everyone is fundamentally bound by their own sense of shame, reputation, and defensiveness. They each worry that something is terribly wrong with them, and that, if it is, no one can find out. They protect themselves. Each of these ministers and noblemen is not only afraid of losing their post, but also of being ridiculed and thought a fool. They each fear their own internal judgment and the judgment of others.

(Art by Henry Clark)

The child is able to blurt out, “But he hasn’t got any clothes!” because he is humble enough to be un-self-conscious. To him, so what if he’s a fool? So what if other people think he’s a fool? Who cares? The emperor hasn’t got any clothes on!

Why we need this story

Who among us is not in some way, especially as adults, bound by shame, reputation, and defensiveness? I will readily admit that I hate looking stupid. How often do I nod along when someone is discussing a topic about which I know absolutely nothing? How often do I opine on areas and issues where it would really be better for me to say, “I don’t know?” How often do I pretend to have read or watched things I’ve never heard of?

As we grow older, we become self-conscious. Sometimes that’s is a good thing — I won’t belabor all of the extensive research about shame that’s been done, but I will suggest the work of Brene Brown and Fr. Stephen Freeman on the subject, respectively (Brown coming from a secular lens, and Fr. Stephen from a specifically Christian lens). They each note that sometimes social shame can compel us to be good to one another. But sometimes, a deep sense of inner shame can prevent us from achieving any real humility. Sometimes, we are ashamed and therefore put up masks to deceive ourselves and others by hiding the self of which we are so ashamed.

Humility is a willingness to be real, even if it’s vulnerable. It’s a willingness to admit, “I’m not that great at certain things yet,” “I mess up sometimes, including in major ways that I need to rectify,” and “I have inherent worth and dignity, regardless,” all at the same time. In Christian terms, it means being able to say “I am small before God” and “I am valuable to Him” simultaneously.

Each of the deceived people in “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is so secretly terrified that they aren’t valuable that they have to pretend they are. They have to put up a front. Their worthiness needs to be based on some clear thing they do or know or contribute, and if they’re falling short of those things, they need to pretend they’re not falling short. We all do this just about all the time.

Only the child is truly free in the story because only the child is willing to look stupid. He’s willing to “bear a little shame,” as Fr. Stephen puts it. The child’s father mocks him and says, “What innocent, naive prattle!” And that’s okay.

How much freer would we all be if we could live according to what’s true rather than what makes us look better? What if it didn’t matter so much how we looked to others but who we were?

Then we would also be able to cry with the child, “He hasn’t got any clothes!” And we would feel the burden of our defensiveness lift. We could live freely according to the truth.